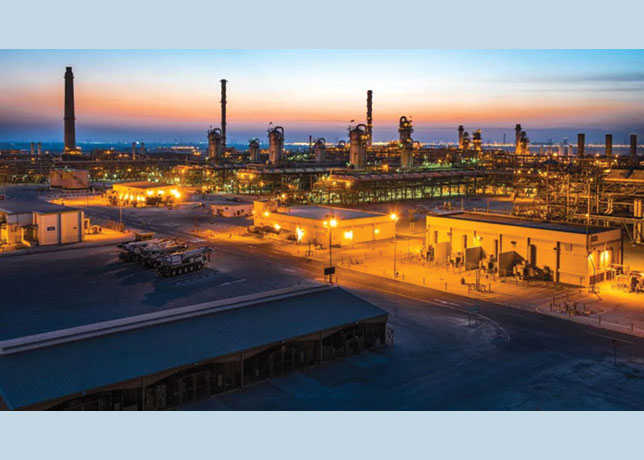

Crescent Petroleum ... awaiting compensation from Iran

Crescent Petroleum ... awaiting compensation from Iran

Crescent won the arbitration last July and it has now entered the damages phase, which could result in an award of billions of dollars based on previous arbitration awards. The outcome is being watched closely by international oil companies

The ups and downs of Iran’s disputed gas deal with Sharjah’s Crescent Petroleum goes some way to explaining why a country that holds the world’s largest natural gas reserves, according to the latest data from BP, still finds itself a net gas importer with only one major export deal in place.

The dispute over a 2001 gas supply deal with Crescent, which has wound on for a decade, has been as much about Iranian politics – internal and external – as it has been about the commercial terms of the contract. Crescent won the arbitration last July and it has now entered the damages phase, which could result in an award of billions of dollars based on previous arbitration awards. The outcome is being watched closely by international oil companies eyeing the prospect that Iran’s hydrocarbons sector will once again open up if a final deal can be done this summer to lift sanctions.

Originally an argument about price, the Crescent dispute ended up involving accusations of corruption and conspiracy in which a British-Iranian businessman, Abbas Yazdi, was roped in to testify and ended up becoming the victim of kidnap and murder in Dubai in 2013. Three Iranians were sentenced to life for that crime in a Dubai court in February. While a direct link was never categorically established, the chief prosecutor Khaled Al Zarouni told the Dubai Criminal Court during the case that Yazdi had given video evidence to the tribunal hearing the Crescent-Iran case in The Hague shortly before he was kidnapped.

That tribunal is a voluntary commercial resolution procedure under the auspices of the International Court of Arbitration (ICA) in Paris, not normally a setting one would associate with international political intrigue. It comprises three arbitrators with one representative from each side, so it is effectively decided by a third independent member. In the Crescent-Iran case, the independent is an Australian barrister.

Ruling in favour of Crescent last July, the barrister dismissed out of hand the various counterclaims put forward by the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC), which had included accusations that Crescent had been involved in a conspiracy involving Yazdi, who was an associate of Mehdi Hashemi Rafsanjani, son of former Iranian president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani.

Mehdi Rafsanjani had been one of the early negotiators in the Crescent contract but was not involved by the time it was completed, according to people familiar with the deal.

Subsequently, the Rafsanjanis fell out of political favour in Iran and were targeted by the regime with accusations of corruption. Last month, Mehdi Rafsanjani was sentenced to 15 years by a court in Tehran. The nature of the conviction was not clear (the BBC Iran service said it involved stirring up trouble after the 2009 elections), but Press TV, a state-run Iranian news company, reported in February that a member of the Iranian parliament, Ahmad Tavakkoli, had accused Mehdi Rafsanjani of arranging up to $15 million in kickback payments for helping Norway’s Statoil win contracts to develop parts of the giant South Pars gasfields.

|

Statoil ... vowing to do no more business with Iran |

Rafsanjani, who returned to Iran from exile in the United Kingdom in 2012, has maintained that the charges were politically motivated. Whatever the internal political machinations in Iran, it is not surprising that international oil companies are wary of entering into new agreements when a deal such as Crescent’s can become so entwined. Statoil, for example, has publicly vowed to do no more business in Iran, after it wrapped up its South Pars contracts, given the present circumstances'.

The environment may improve since the election of Hassan Rouhani as president in 2013 brought back a more technocratic group to run the hydrocarbon sector under the oil minister Bijan Zanganeh. As soon as he was put back in charge, NIOC began detailed planning of how to lure back international oil company investment and expertise, says Peg Mackey, an Iran expert at the International Energy Agency in Paris.

Zanganeh, who ran the oil sector under former president Mohammed Khatami [who was president when Crescent negotiated its deal] is widely respected by the international oil companies and credited with increasing Iran’s production during a first round of US sanctions,' she says.

But even if he would like to resolve the Crescent deal amicably – by agreeing to revive it or, more likely, agreeing terms to end it so he can move on and work on bigger, more important projects – he may feel boxed in.

Zanganeh is a very competent minister. The only thing is the Crescent deal was negotiated under his watch,' says an Iranian analyst, who did not want to be named. He may feel it’s best to kick this down the road four, five years to when he is no longer minister. That’s the ideal solution for a bureaucrat in his situation.'

Agreeing a big settlement might be seen as an admission of failure over the deal. NIOC sent gas through the pipeline, as a test, to Dana Gas’ facility at Sharjah at one point in 2010 before pipeline leaks forced it to halt. There are provisions to negotiate up the extremely low price originally agreed but it seems unlikely the deal will overcome additional political obstacles in the way of Iran gas export agreements such as Crescent’s.

As Homayoun Falakshahi, a Middle East analyst at the energy research company Wood Mackenzie, points out, subsidised natural gas has driven explosive domestic demand growth over the past decade, more than doubling consumption in Iran. NIOC has also contributed to the growth by injecting huge amounts of gas into oilfields to keep production rates up.

Thus, even though it has doubled production in 10 years, internal demand means Iran has had to import more gas from Turkmenistan than it exports to Turkey, its one major export contract.

The Turkey deal, as it happens, is also in dispute and is due for an arbitration decision next month. In that row, Turkey argues that it is paying far too much for Iranian gas – some 20 to 30 per cent above the cost of Russian and Azerbaijani gas.

Turkey has already won an arbitration from the ICA, in 2009, which awarded it $900 million after Iran had cut supplies for two weeks. Iran traditionally has had a desire to use gas to enhance its strategic relationship with neighbours,' the anonymous Iranian analyst says. But that has been pushed out by competing domestic priorities – and sanctions haven’t helped, of course.'

Iran has been talking for decades about piping gas to Pakistan and has completed most of the pipeline work on its side of the border. Last week, after the framework deal was reached on its nuclear programme, China’s energy minister said Chinese companies would build the $2 billion Pakistani side of the pipeline.

But Iran has signed dozens of memorandums of understanding about deals with countries throughout the region – more than 20 with Oman alone – to supply gas from its vast fields and none have come to fruition. Indeed, in the past couple of years it has cancelled contracts with China’s National Petroleum over disputes about performance in developing phases of its giant South Pars offshore fields, which contain about 40 per cent of Iran’s gas reserves.

It is going to require hefty investment,' says Mackey. To that end, Iran’s oil ministry has prepared a new upstream contract to lure foreign oil companies and top officials from a number of western oil majors have already met publicly with Zanganeh to express their interest.' That will require rebuilding confidence after the last wave of contracts in the 1990s proved disastrous. The main question for the international oil companies would be the rate of return. Some of those previous buy-back deals ended up having negative returns,' Falakshahi says. Now the threshold would be something like 15 per cent.'

The potential rewards in Iran’s gas sector are huge. In its latest review of world hydrocarbon resources, BP put Iran’s reserves at about 33 trillion cubic metres, or 18 per cent of the world total. That is above Russia’s estimated 31 trillion cubic metres, in second place with 17 per cent of world reserves, although Iran’s share of world gas exports is negligible. Companies will be looking for signs from Iran that new contract terms will make investment worth it in a low oil and gas price environment.

They will also be looking for reassurance that they will not be bogged down in endless disputes when the market improves.