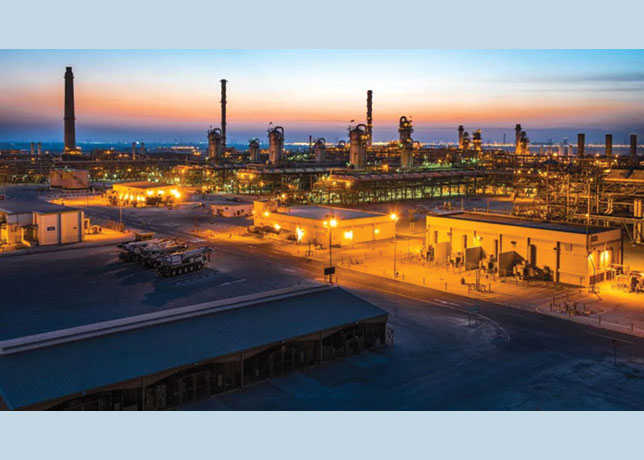

Khadir

Khadir

Determining VAT’s impact on oil and gas activities is often complicated by the need for businesses to respond quickly or lose money, say two experts from Keypoint, one of the GCC’s leading professional business services providers

As Bahrain gears up for VAT from January 1, 2019, two experts from Keypoint, one of the GCC’s leading professional business services providers, answer a number of vital questions related to VAT.

Mubeen Khadir, the head of tax, and George Campbell, an associate director recognised as a leading technical expert on VAT, point out that, despite the prospects of increased income from its recently announced oil and gas discoveries, Bahrain still needs to diversify its sources of revenue.

How will Bahrain’s recently announced oil and gas reserves impact plans for VAT?

The announcement of significant oil and gas reserves off the west coast of Bahrain has injected welcome optimism into the kingdom’s oil and gas sector and the broader local economy. A number of observers have suggested that the find, coupled with improving oil prices, could see a drastic improvement in Bahrain’s budget position, alleviating the IMF’s concerns over Bahrain’s long-term economic and fiscal strength. If the reserves are as significant as originally suggested, and recovery less technically challenging than first feared, why does the kingdom need to introduce VAT with all of the disruption that the new tax will bring in its wake?

The answer is simple. Bahrain needs to diversify its sources of revenue, looking beyond hydrocarbons to more sustainable sources. While Bahrain does not levy income tax on individuals and corporates, tax is not a new concept to the oil and gas sector (with a corporate tax of 46 per cent on any oil and gas company extracting or processing hydrocarbons) or to the kingdom in general, with levies chargeable on supplies made by leisure industry, particularly in the country’s hotels and restaurants. Add to this, the excise tax introduced at the end of 2017 on tobacco, soft drinks and energy drinks and the more recent postal tax, and it is clear that Bahrain is looking towards the future, seeking to establish stable and sustainable non-hydrocarbon sources of income. With oil and gas still contributing well over three-quarters of Bahraini state revenues, VAT obviously has an important part to play in broadening fiscal revenues and should, therefore, be seen as part of a broader continuum.

|

Campbell |

In early 2017, all six GCC member states committed to VAT by signing the Unified VAT Agreement for the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf – the GCC VAT treaty. The treaty sets out the legal framework for VAT’s application, as well as many fundamental VAT concepts. Saudi Arabia and the UAE then published national VAT laws and regulations and implemented the tax on January 1 2018, with the expectation that the other GCC states would follow suit. Bahrain will be the next GCC state with a VAT implementation date of 1 January 2019 now confirmed. It is therefore critical that businesses – particularly in a sector as complicated as oil and gas – begin to prepare for the tax. Although the law has now been released, the implementing regulations – which explain exactly how VAT will be applied – have (as of the date of writing this article) still not been released.

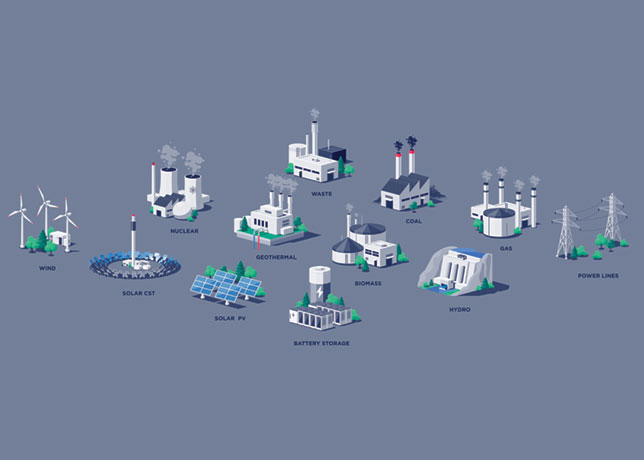

How will VAT impact oil and gas businesses?

Oil and gas products are generally subject to VAT. In Saudi Arabia, oil and gas products are subject to the standard rate of VAT, unless they are exported, in which case they are zero-rated. The UAE and Bahrain have zero-rated the supply of crude oil and natural gas, with Bahrain extending the zero-rating provision to also include any oil, oil derivatives and gas. Further details expected in the Bahrain VAT regulations should clarify the extent of the zero-rating – such as whether the zero-rating provision applies to petrol at pumps. Suppliers of zero-rated oil and gas products are likely to almost always be in a VAT refund position, as they should be entitled to recovery of VAT incurred on their costs, which is likely to result in significant cash flow issues, depending on the timeframe given for refunds of tax. This may be a bigger issue in Bahrain than elsewhere in the GCC, owing to the potential breadth of the zero-rate application and the export profile of businesses in the kingdom.

While VAT usually means higher prices for consumers, the demand for oil and gas products is fairly inelastic and sales should not be significantly impacted – particularly against the backdrop of recent, significant hikes in the price at the pump. With Brent crude rising from just over $50/bbl to just under $80/bbl over the last 12 months, this could – at least from that perspective - be as good a time as any to adopt VAT.

VAT incurred on capital expenditure significantly impacts cash-flow. Large-scale capital expenditure is often incurred at the early stages of an oil & gas project while supplies (which means income flow) are likely to occur some years later. Depending on the turnaround time for tax authorities to process and approve VAT refunds, business may be left waiting for VAT refunds.

For oil and gas businesses, due to inherently stable demand, VAT’s impact shouldn’t be measured by its impact on consumer spending - but by the technical complexity of the tax, the procedures and knowledge required to comply with new regulations, the need to dedicate scarce resources to determining, calculating, accounting for and paying VAT to the tax authorities, and cash flow pressures.

Why is VAT complex for oil and gas?

Cross-border activity and the fact that work can be carried out onshore and offshore tends to complicate VAT for most oil and gas companies. As a result, oil and gas businesses often have some of the largest and most experienced in-house VAT teams outside of the consulting profession. Determining VAT’s impact on oil and gas activities is often complicated by the need for businesses to respond quickly or lose money – if a component breaks, interrupting operations, the financial imperative is often to replace the part as soon as possible, regardless of the VAT implications. Some huge ‘locked-in’ VAT costs have already been created in the GCC due to poor planning in relation to the importation of goods, coupled with the need to respond quickly to external business pressures.

Mistakes are often only identified after an action has been taken. Resolving the situation can become a case of damage limitation. The cost of mistakes can soon add up, where the tax authorities determine a treatment is non-compliant and levy assessments and penalties. Oil and gas businesses have to balance running business against complying with their tax obligations.

In the formative stages of VAT, even with the best will, it is often difficult to fully comply with the law as VAT guidance (particularly on an industry basis) may be rudimentary, leaving businesses to make difficult judgement calls on more challenging VAT issues. The GCC has some way to go before it can give the industry all information it needs – there is, for instance, no equivalent yet of the UK’s 90-page North Sea Oil and Gas Memorandum. In the meantime, businesses are likely to contact the tax authority for guidance. However, as tax authorities themselves are still learning and upskilling, they may struggle to correctly guide businesses, meaning an increased reliance on consultants.

What about cash flow, administration and contractual matters?

Cash flow and working capital impacts are closely linked to cross border activities and trade. When importing goods from abroad, businesses must pay VAT to the tax authority before the goods are released into free circulation. This leaves affected businesses initially out of pocket until a claim for credit or refund can be made to the tax authority.

As we have already seen on the supply side, suppliers who export oil and gas products, or supply qualifying oil and gas products in the UAE and Bahrain, can apply the zero-rate of VAT. As they are entitled to recover local VAT suffered in the course of making those supplies, they will be in a net refund position. However, refunds may take some time to process and receive. Spare a thought for Saudi ‘repayment’ traders who have been promised that refunds will be paid within 60 days ‘of approval’ by GAZT. Bahrain is yet to qualify its approval and refund time frame. Businesses investing large amounts of capital, culminating in a one-off repayment, may also find their cash flow position negatively impacted.

Another common issue is long-term contracts which did not contemplate VAT. Where supplies made under those contracts are taxable at five percent and extend into a VAT-live regime, VAT is payable. Where customers accept the additional VAT charge – because they can pass the cost on down the supply chain – this may not be an issue. However, if contracts are silent on VAT, agreed considerations are deemed to be VAT inclusive, and the supplier may have no legal right to charge customers additional amounts. If a customer - perfectly legally - refuses to pay the extra five per cent (or part of that five per cent), the supplier remains liable to pay the VAT amount to the tax authority, and its bottom line will be negatively impacted.

What should oil and gas businesses do now?

Businesses outside Saudi Arabia and the UAE need to get moving. They cannot afford to wait – if businesses in the UAE had waited on the final executive regulations, they would have had 33 calendar days to prepare. The implementation process can be relatively standard. Assess operations to better understand the impact that VAT will have. Identify risks. Prepare and action plans to mitigate, eliminate, or otherwise cope with those risks. Assess the capability of IT systems. Engage a systems integrator – internally or externally – to make changes, automate VAT processes and comprehensively test those processes before going live. Review document templates to ensure they are VAT-compliant. Train people, or recruit staff with the necessary skills to operate in a complex oil and gas environment.

This, however, is easier said than done. For example, long-term contracts have caused significant issues in Saudi Arabia and the UAE, so oil and gas businesses should review contracts to assess where the money to pay VAT comes from. Where there is any doubt, start communicating with customers.

One important finding from the UAE and Saudi Arabia is that there were limited competent VAT specialists who both understood the industry and the complications of VAT. Engaging chartered accountants or internal auditors who have suddenly recast themselves as VAT experts – while apparently attractive from a budgetary perspective – is unlikely to help you with this significant challenge.